Figure 1: A busy central London scene with people everywhere.

Behaviour is the raw material of research

For all our differences and similarities it is people and our behaviour which needs to be closely observed if we are to understand what makes interaction truly meaningful. In my last article I outlined a simple model ‘the meaning dimension’ to help consider how we can understand the significance of meaning. The aim of the article was to introduce the meaning dimension as a scale that could be considered for interaction design. It also reinforces my position that truly great and engaging interactive experiences are meaningful and that’s because our need to understand represents a fundamental human need: we need to make sense of the world. This article focuses on discovering and understanding what is meaningful in interaction design. Researching meaning raises many challenges. Meaning can be both obvious and ambiguous. We can interpret an event or situation in exactly the same way and yet, we can interpret it completely differently. It represents an interesting design challenge and this is why I consider it so important to explore and understand its implication. I’ll outline other aspects that I think are critical in an attempt to frame it correctly so we can focus on researching what factors make interaction meaningful. Meaning is not an all or nothing experience. It is scaler. This is the idea underpinning the meaning dimension. Our experiences are not either meaningful or meaningless. They are influenced by our actions and behaviours and as a consequence we rate them as more or less meaningful.

The Iceberg Model of Meaning

Figure 2: Iceberg model of meaning.

Figure 2: Iceberg model of meaning.

Figure 2 reveals that on the surface we may see very little of the iceberg yet we also know that below the water lies a much bigger structure. Meaning is a lot like an iceberg. The surface meaning can be obvious whereas the deeper meaning can be ambiguous and open to interpretation. Let me elaborate, we can see the shape and scale of an iceberg sitting above the water line. Yet, below the water line we can not accurately predict an iceberg’s shape and scale just by looking at it from the surface. Meaning is similar in this regard because the important bits we are interested in understanding are the emotional effects and critically, the relationship (interaction) between the surface meaning and deeper meaning. Both factors influence each other and affect our behaviour; we can’t have one without the other.

On the surface we experience meaning when things quickly make sense. Whereas, the deeper meaning affects how we feel about an experience. However, below the surface we cannot be accurate about what’s involved in helping us shape the deeper meaning. We may at best only be able to gain a partial understanding of what is happening below the surface and this is the dichotomy interaction designers have to recognise. It does not limit the quality of the interaction we can design but it does mean we have to accept we have limited knowledge and understanding of the factors that influence the deeper meaning. The deeper meaning we feel may also be counter-intuitive so working it out may be difficult because we cannot simply make a guess and get it right; it transcends ‘common sense’ because it may neither be common or obvious. This means applying a common sense approach may not reveal the details we need to understand and determine what is ‘actually’ driving the deeper meaning we feel.

The relationship between surface meaning and deeper meaning

To understand what is meaningful we have to delve much deeper below the surface. What people say is one thing; what they do another. What we feel when we are interacting with any digital technology adds an extra level of complexity that also needs to be appreciated. The challenge for the interaction designer is accepting that to discover what it meaningful for an audience we have to attempt to discover the thinking and the feeling that will generate meaningful interaction.

On the surface everything can seem meaningful

Figure 3: The beautiful Annabelle Norris (my daughter at 18 months)

Figure 3: The beautiful Annabelle Norris (my daughter at 18 months)

Let me elaborate. It’s the middle of the night and I hear my daughter crying, and instantly, I understand: she is upset. The understanding required to act appropriately does not need any deep analysis on my part. I instantly get what it means and I get it quickly. This is the power of surface meaning. My immediate understanding requires little cognitive processing and my behaviour is reflex-like; I go to Annabelle to see what’s wrong. However, there is a deeper meaning which in fact is far more illusive. It may not even be possible to accurately understand or define it because the deeper meaning is more emotional and unconscious rather than rationale and unconscious. So, why is Annabelle crying? I know she is crying, and therefore she is upset in some way, but in what way, and more importantly, why? Is she teething, cold, just had a nightmare or wants a cuddle? Interaction design is no different – we need interaction experiences to be, and feel meaningful. The surface meaning provides the facts but not the feelings. As interaction designers we need to learn how to dive below the surface. We have to help people make the connections between what they think and what they feel.

Humans are very complicated

Once we accept the fact that we are complicated we have taken the first positive step in the quest to deliver meaningful interaction. The often touted common sense approach (e.g. it seems obvious) does not reflect how counter-intuitive our actual behaviour is, let alone its complexity. Each and every single one of us is filled with memories, dreams and ambitions and this makes trying to research meaning from a rational perspective one of the first ideas to question. We are not rational, we are rationalising. In fact, we are more emotional than rational. We have moments of rationalisation. Like the iceberg model in figure 2 the surface meaning is the smaller component that is influenced by the larger deeper meaning component and when they are combined together they will shape our understanding. Most of our decisions on a daily basis will be driven by some form of emotional factor rather than just thinking and reasoning. Surprisingly this is true for even the most logical people.

This represents another powerful insight about human behaviour because what ever we may do in the lab or the field to observe and understand human behaviour we must appreciate that we may not be observing a true reflection of actual behaviour. This should not stop us but it should provide the necessary caution required to remain objective. The greater our understanding of the interaction between the surface and deeper elements the better the interaction design we deliver and the closer the match with our ‘actual’ behaviour.

Sensing patterns

Figure 4: Four images: the first image is a square the last image is a house.

Figure 4: Four images: the first image is a square the last image is a house.

One of the things that constantly fascinates and intrigues me is our ability to make sense of patterns with very little information. Looking at the four images in figure 4 you can see the evolution of a house (4) from a simple square (1). When did you see a picture of a house? Figure 4 forms part of very simple test I do with people to show them how good they are at recognising and interpreting patterns. I start by drawing a square and asking ‘what’s this’? Most people say a square. However, once the additional element is added to the square in the second image pretty much everybody says it’s either a ‘house’ or a ‘cube’. When more elements are added for the third image everybody I’ve asked so far has said a house. In fact it’s pretty incredible that with so little information you are able to make this leap. Whilst images 2 and 3 are much less complex than image 4 we can quickly anticipate and accurately predict the pattern because the surface meaning is so obvious. We can quickly fill in the gaps and we work out the surface meaning very quickly when we understand the underlying elements of a pattern. So, helping people to generate surface meaning can and will change the way that people interact and more importantly how they feel. If we want people to feel good about interacting with our products or brand we need to ensure that the surface elements (meaning) can be quickly and accurately interpreted. What is surprising is that surface meaning is not restricted to the visual channel because the same holds true for our other senses. You hear a few notes and you know the melody or song. You take a sip from a cup of tea and you immediately know if the milk has gone off. Our pattern recognition abilities are an amazing talent and this is because our brains and cognitive systems are amazing. Colin Wilson in his book Strangers to Ourselves (2002) points out that we are processing upwards of 11,000,000 pieces of sensory information a second! However, we can only attend to 40 of those pieces of information in any given second. That means 10,999,960 do not even get noticed consciously, yet, the information is not disregarded, it is processed. However, its effects may remain invisible to us. This is an amazing insight that again demonstrates how amazing we are and more importantly supports the idea of the deeper meaning (unconscious thinking) being more significant in shaping what we consider meaningful. We have to be able to design interaction experiences knowing the limitations of our cognitive systems so increasing the meaning people experience.

So how does this apply to the design of experience and interaction?

Figure 5: Nomensa homepage showing the navigation, carousel and a content features highlighted which are all established interaction design patterns.

Figure 5: Nomensa homepage showing the navigation, carousel and a content features highlighted which are all established interaction design patterns.

The more established the interaction design patterns being used the greater the level of surface meaning and therefore the quicker it is to recognise each element and the easier they are to use. The level of digital literacy required to use the Nomensa homepage shown in figure 5 will be fairly low and therefore this makes it easy to use for the vast majority of people. There are no mysterious patterns to understand or complexities to unravel. What I also consider interesting about interaction design is how we can shape the experience into something that feels authentic and natural. Whilst the web is a growing and dynamic system of information we can only experience it as a collection of stationary elements such as web pages that are in turn composed of content and functionality. When we move from element to element this is often described as a user journey because we are moving through multiple web pages with multiple web elements in each page. For example a user journey may be composed of a series of pages, yet each page is treated as a single page regardless of the number of pages involved because we consciously process information as a sequence, one bit at a time, and not, dynamically. Therefore, our actual browsing experience is not dynamic, it is sequential. We process everything as a single stream of consciousness rather than simultaneous (multiple) streams. As previously mentioned the web may be dynamic however from a cognitive perspective we can only process one element at a time. The concept of multi-tasking has been defunct for a while and now considered a misnomer and what we actually do is task-switching. We can quickly switch between tasks but we cannot process more than one task at a time because of the limits of our cognitive processes and underlying neural circuitry. This represents another interesting conundrum for interaction designers. Do you focus on the users’ goals or on their behaviour? The right answer is both. Let me elaborate and to do so I want to introduce a very powerful psychology theory: Reversal Theory.

Using Reversal Theory to explain what is meaningful

Imagine that you are about to browse the web. The behaviour is browsing and you may or may not have a goal. Let’s assume you don’t have a goal other than to pass time and see what takes your fancy. You are in a paratelic state. Suddenly you remember that you need to look at holidays because you are thinking about a family holiday, so you jump off Apple trailers and head to Google to begin your search. You are now in a telic state. We have switched (reversed) from one state the paratelic to the telic state. Michael Apter’s book Reversal Theory: The Dynamics of Motivation, Emotion and Personality (2007) is a good starting point to understand the theory in more detail and how we switch (reverse) between meta-motivational states (e.g. arousal-seeking vs. arousal-avoiding states) which directly affects arousal and therefore our behaviour.

Building deeper meaning: creating the all important ‘flow’

Imagine you are browsing a site to get a feel for an organisation and whether you trust it enough to consider buying something. You may start off in a paratelic state but as the need for information increases so will your arousal or arousal-seeking behaviour and you will reverse into a telic state because you have shifted from simply browsing the site to seeking specific information that will satisfy a goal. However, the site may be presenting multiple cues which could nudge you into starting a task that will not support you and could artificially reverse you out of your desired state, e.g. you become frustrated and switch back to a telic state. At this point the task has been undermined and you are more likely to abandon than continue. Presenting multiple design cues that can trigger a telic response response can be a risky design strategy that is all too often taken and it works to reduce our perceived control. As a rule of thumb we need to very careful about removing control because we tend not to like it unless we allow it. However, removal of our sense of control can be very commonplace online because websites are not set-up to reflect our behaviour especially our meta-motivations. They are typically set-up to reflect goal behaviour and therefore the tasks they want their audiences to complete. Conversely, there may be no goal we want to complete and so we end up being forced to do something we do not want to do. In effect, we are forcing people rather than guiding them – who likes that?

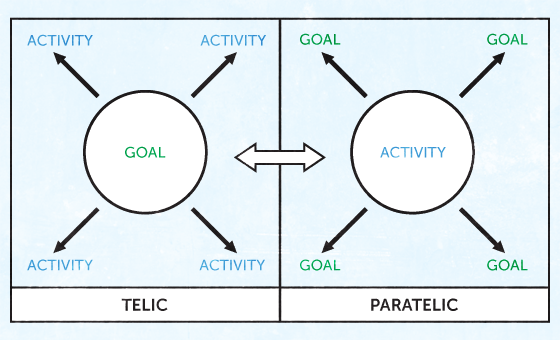

Figure 6 Schematic relationship between goals and activity and how they can reverse between telic and paratelic modes.

Figure 6 Schematic relationship between goals and activity and how they can reverse between telic and paratelic modes.

In figure 6 above we can see the relationship between the two states: telic and paratelic. In the telic state the goal is the focus and the activity the background. Whereas, in the paratelic state the goal is the background and the activity the focus. Figure 6 shows how we can switch (reverse) between the two states and consequentially the ‘goal’ and ‘activity’ can also switch. If we take the example of finding a specific piece of information on a website (e.g. you are looking for a specific product and want to read the associated product information) you are likely to be in a telic state and the goal will be your focus. If the methods you are using to find the information do not prove fruitful you may switch states (e.g. from telic to paratelic) as you explore alternative methods of locating the information. You may eventually switch back again to a telic state once you have re-focused on the goal. This simple example above illustrates how Reversal Theory can be used to explain our digital interactions and how we can switch at any moment between goal-focused and activity-focused behaviour. To design meaningful interaction we need to consider both our activities and the goals we may wish to complete as a dynamic relationship that is in a constant state of flux. The over emphasis in the design process of establishing goals and tasks at best can only reveal one half of the behavioural equation. This approach will need to fundamentally change if we intend to deliver better interaction designs that can produce more meaningful and therefore more authentic experiences. The value of reversal theory is that it can provide a better method for representing human behaviour more holistically. It helps us introduce activity as a vital ingredient in the design process which can often be negated or avoided because of the over emphasis on defining ‘goal-driven behaviour’. There are times when we may not even have a goal or the goal may be so unstructured or even unconscious that it can make it too hard to design for with any level of accuracy. Yet, if we understand the underlying activity that supports the goal we are supporting successful reversals from activity to goal and back again without forcing people to interact in a purely goal-focused way because they may be in a paratelic state (e.g. browsing and skimming through information). I’ve coined the phrase ‘forced abandonment’ to reflect digital interactions that actually cause us to leave (or switch state) before we are ready to leave. You are literally forced to abandon the experience because it is either not providing the information you want, or it’s trying your patience (causing frustration) and generally reducing your control. There are many other reasons but hopefully you get my point. To build the feeling of flow that comes from a deeper immersion with an interactive experience we have to ensure people are not forced to abandon and are allowed to leave when they are ready so that it feels natural to do so. The more time we spend interacting with an experience the more invested we feel and therefore the greater the level of engagement, and as a consequence, the flow we feel. Our emotional feelings amplify when we spend more time doing something we enjoy and this is one of the reasons why games are so powerful and we connect with them much more deeply – they encourage us to ‘keep going’. More importantly it is one of the critical reasons why people are looking to apply ‘gamification’ and emotional design principles to the design of interactive experiences and make them more appealing and therefore engaging.

Forced abandonment vs Natural abandonment

Forced abandonment is the opposite of natural (controlled) abandonment, an effect that I have observed when people are satisfied with what they have done and do not feel they need to interact any further. Natural abandonment allows a person to exit a task knowing they can return to complete it should they need too. It puts the control into the hands of the user. This is one of the reasons why looking at user experience through a goal-driven lens does not take into account the rich and complex behaviour we bring to everything we do. You cannot subtract behaviour from the interaction experience and reduce it to a set of goals and therefore it is better to account for it by designing-it in.

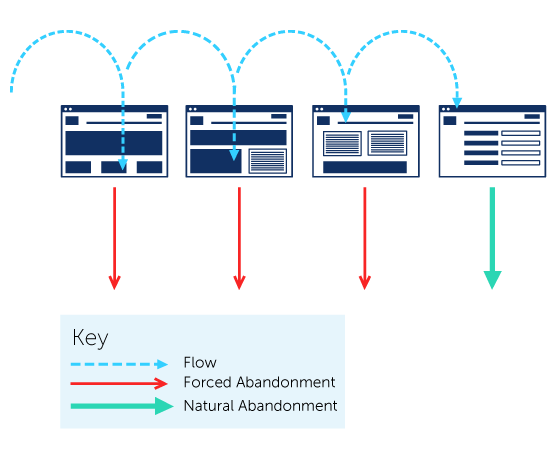

Figure 7: The ‘flow’ of interaction.

Figure 7: The ‘flow’ of interaction.

In the image above we enter an experience which is composed of pages with content. Depending on the surface meaning we either work out how to interact or we abandon. There is a fine line between whether we stay (continue) or whether we leave (exit). So, as we move from page to page, element to element we start to generate a feeling of flow and the experience will start to take on greater significance. Therefore, the feeling of flow in the interaction experience dictates whether we will continue or abandon. The greater the flow (deeper meaning) the less likely we are to be forced to abandon and when we do, it is natural abandonment. Let’s discuss a simple example. You find yourself browsing on the web and you come across an interesting twitter link which gets your attention, you select the link and visit a blog with a relevant post you are interested in and you read it and that leads you to another site, and so on. You have passed from a paratelic to telic state and back again. Alternatively, you favourite the tweet for later reading and we can see how you’ve switched from a paratelic to telic state and then back to paratelic state (e.g. from browsing to reading and then back to browsing). As previously mentioned we have to slow down to make sense of an interactive experience at the surface level. As we move between pages or page elements it is the surface meaning that will keep our attention or will break it and force us to abandon. This can introduce problems because if we are forced to stop because of poor usability, confusing form-design or poor accessibility it may force us to go somewhere else. We typically don’t leave the web when we are forced to abandon we just leave the current experience (with a less than positive experience). Unfortunately, we are still forcing too many people to abandon digital experiences because the investment in the surface level, and more importantly the understanding of what is meaningful to the audience at this level has not received appropriate investment in time and effort. The consequence is ‘forced’ abandonment and represents a massive commercial risk. Let’s take a common assumption about the web that many people still believe it to represent a commercial panacea of self-service yet it is this very perception that causes abandonment because it does not make us feel anything and often we are left actually feeling emotionally flat or frustrated. We have to work out how to design interaction experiences that feel meaningful and authentic so we can deliver richer and deeper experiences. Self-service only works when people can quickly and easily familiarise themselves with an experience and this requires that we feel in control rather than out of control. Reversal theory provides a mechanism for designing interaction that places control at the centre of the interaction experience whether it is either the goal or the activity because both can have focus depending on our meta-motivational state.

The closer you get to the interaction the greater the level of behaviour you will observe

Once you’ve decided that you want to understand and deliver a meaningful experience you are also accepting that there is a real need to observe how people actually use technology so that the requirements reflect both their goals and activities. The closer you get, the more realistic the observations and the better the quality of the insights we can discover. It is the insights that can turn an average interaction into something wonderful. So a number of questions need to be asked when we are researching meaning and these may include:

- We need to establish first and foremost why people do what they do? Behaviour is the essential ingredient. We need to design meaningful interaction and the more we know, the greater our appreciation of the behaviour and the better the final design.

- We need to to establish why people use technology in the way they do? People are different and that means they may use technology differently. Understanding their differences and similarities can make a real difference to the final design. This allows us to more accurately represent different audiences’ needs which will better reflect their patterns of usage.

- We need to establish what motivates, interests and excites people? Knowing what motivates an audience can help to determine the flow of interaction and keep their attention and interest focused as they transverse an experience.

- We need to establish how people want to use technology? Knowing how people actually want to use technology allows us to design for changing needs and greater levels of skill (or lower levels of familiarisation). More importantly, it allows us to differentiate between ‘activities’ and ‘goals’ and ensures they are appropriately represented so that contingent switching is allowed (supported), e.g. people can easily move between tasks and activities.

In conclusion the goal of researching design from the the perspective of meaning is to provide behavioural insights that add real significance and therefore help to deliver a more understandable and engaging interaction design experience. Ultimately, this is the road towards long-term customer and client engagement. Too much focus has been placed on discovering and defining goals. Whilst this approach still represents a valuable contribution it needs to be accurately balanced (activities). We need to treat interaction design as a holistic process and not just pay it ‘lip service’. The next part of the interaction design puzzle is translating all the research, analysis and insight into the all important ‘actual’ design and will be the focus of my next article covering meaning.

UX Research is at the very heart of what we do and a key component in any design and build work we do. Getting the research right at the start of your project will ensure that your project will run smoothly and meet the needs of your customers. If you would like to speak to us about how we can help you with your UX research then please do not hesitate to give us a call 44 (0) 117 929 7333, in the meantime take a look at our UX research services.

We drive commercial value for our clients by creating experiences that engage and delight the people they touch.

Email us:

hello@nomensa.com

Call us:

+44 (0) 117 929 7333